The Principles of the Covenants

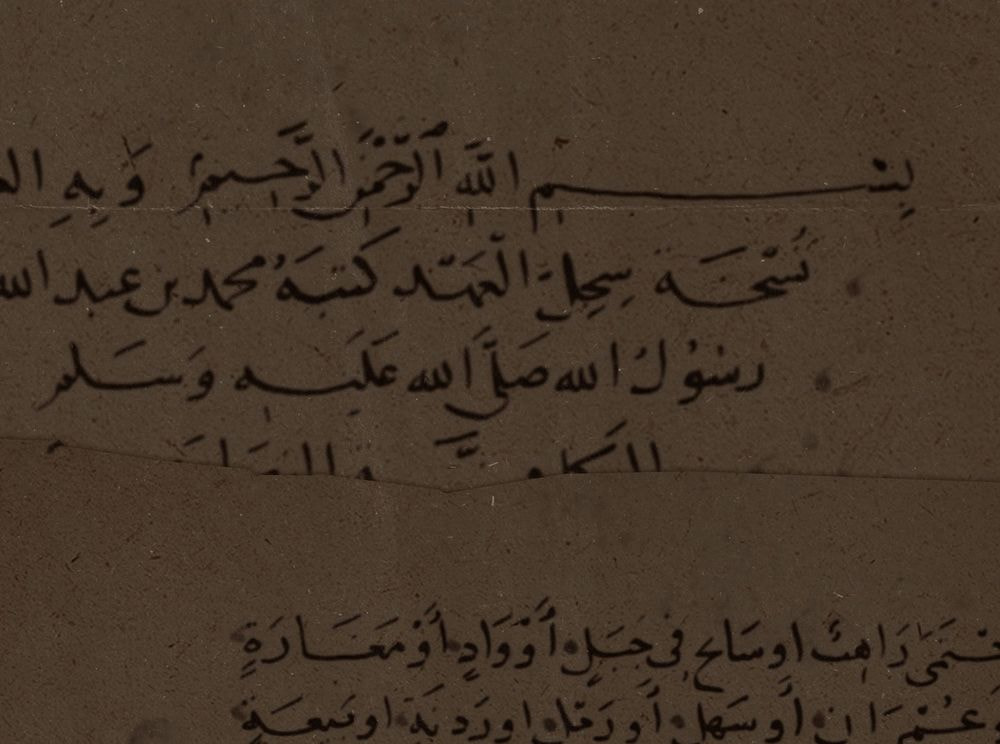

Surviving copies of the Covenants sent to the Christians of Najran and the monks of Mount Sinai are considered some of the most thorough and detailed documents discovered so far, with important and timeless stipulations.

The Arabian Peninsula at the time of the Prophetﷺ was marked by intertribal fighting and there were continuous wars between the world’s superpowers, the Byzantines and the Sasanians. By laying out principles of good governance and peaceful coexistence in his political documents, the Prophetﷺ intended to bring about justice to the whole of humanity, which at that time was unprecedented.

The main principles of the Covenants are:

Freedom of Belief

One of the most striking aspects of the Covenants is their emphasis on the right of non-Muslim communities to continue to practice their religion whilst under Islamic rule. Prophet Muḥammadﷺ declared in the Covenants that no non-Muslim shall ever be forced to embrace Islam, in adherence to an instruction from God in the Quran (Qurʾān):

“There is no compulsion in religion.” (Chapter 2, verse 256)

What’s more, Christian and Jewish communities maintain the right to their own religious leadership and the freedom to orchestrate their communities under their own laws and supervision. In the Prophet’sﷺ treaty with the Jews and Christians of Najran, the Prophetﷺ stipulated:

“No bishop, monk, or rabbi shall be removed from his position.”

In a period of time defined by war between superpowers and inter-tribal fighting, this clause was a rare and true solution for the purpose of creating a harmonious society. The semi-autonomy experienced by the people who received a Covenant from the Prophetﷺ is as groundbreaking today as it was then, considering the degree to which prejudice and racism is still rife in modern nation-states of the 21st century.

Protection of Places of Worship

Prophet Muḥammadﷺ also stipulated that if churches needed repair, then Muslims were obligated to help Christians rebuild them.

Churches, synagogues, and other places of worship belonging to the communities included in the Covenants of Prophet Muḥammadﷺ were to be protected, and indeed, Muslims were forbidden from destroying or occupying them.

One of the most famous examples of this clause in action can be seen in the example of Umar ibn al-Khattab (‘Umar ibn al-Khaṭṭāb), who was a revered Companion of the Prophetﷺ and the second caliph of Islam. Following the conquest of Jerusalem, Umar granted a Covenant to Patriarch Sophronius, guaranteeing the wellbeing of all Christians living or making pilgrimage to the Holy Land. When ‘Umar was invited to pray in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre by the Patriarch, he refused, for fear that later Muslims would appropriate the space with the excuse that ‘Umar had once prayed in the Church.

The Prophet Muḥammadﷺ also stipulated that if churches needed repair, then Muslims were obligated to help Christians rebuild them. In Christian sources, it is reported that Muawiya (Mu‘awiya), the first Umayyad caliph of Islam, helped to rebuild the Church of Edessa in modern day Urfa, after an earthquake had destroyed it in 679 CE.

Economic Justice

The Covenants also cover finances in an Islamic society. A tax called the jizya was levied on non-Muslims which exempted them from military service.

The Prophetﷺ stipulated in the Covenants that although the jizya would be required from non-Muslims, it was to be taken from them only if they could afford it and at an agreed and satisfactory rate. People devoted to religion, such as monks and priests, as well as the poor, were exempt from such an obligation. The Muslims, on the other hand, would pay a tax called Zakat (Zakāt) (the 2.5% of the surplus wealth of Muslim individuals that is an obligatory form of charity). This was not imposed on non-Muslim community members.

In line with the rulings around religious freedom, Christians and communities of the Covenants were permitted to administer financial dealings within their own communities as long as they upheld the Covenant with the Muslims.

Marriage Dealings

The Covenants extended to non-Muslim subjects of Islamic societies, a right to religious freedom that rendered them as the dhimmi (dhimmī) or protected peoples.

In an Islamic society, there were strict rulings around marriages, both within the Muslim community and in interfaith marriages. It’s important to note that in the research around the Covenants so far, the stipulations on marriage only explicitly referenced Christian communities.

Muslims had no precedence over any other community under Islamic governance, and this extended into marriage dealings. The Covenants with Christians stipulate that no Muslim shall enter into a marriage with a Christian woman without the permission of her family, and that a Christian woman has the right to retain her right to practice her belief throughout the marriage. Muslim men were strictly prohibited from coercing their wives into converting to Islam.

The Prophetﷺ himself was married to wives of Jewish and Christian heritage, among them Safiyya bint Huyayy (Ṣafiyyah bint Ḥuyayy) and Maria al-Qibtiyya (Māriah al-Qibtiyya) respectively. The clause around marriages played a crucial part in conveying the dignified role that the people of the Covenant played in Muslim society.

These main themes are thought to have helped establish a form of pluralism between Muslims and non-Muslims in Islamic societies. The Covenants extended to non-Muslim subjects of Islamic societies, a right to religious freedom that rendered them as the dhimmi or protected peoples. The end clause is a famous hadith (saying) from Prophet Muḥammadﷺ, where he says:

“Whoever harms a non-Muslim living under our protection {dhimmī}, I shall be his foe on the Day of Judgment.”